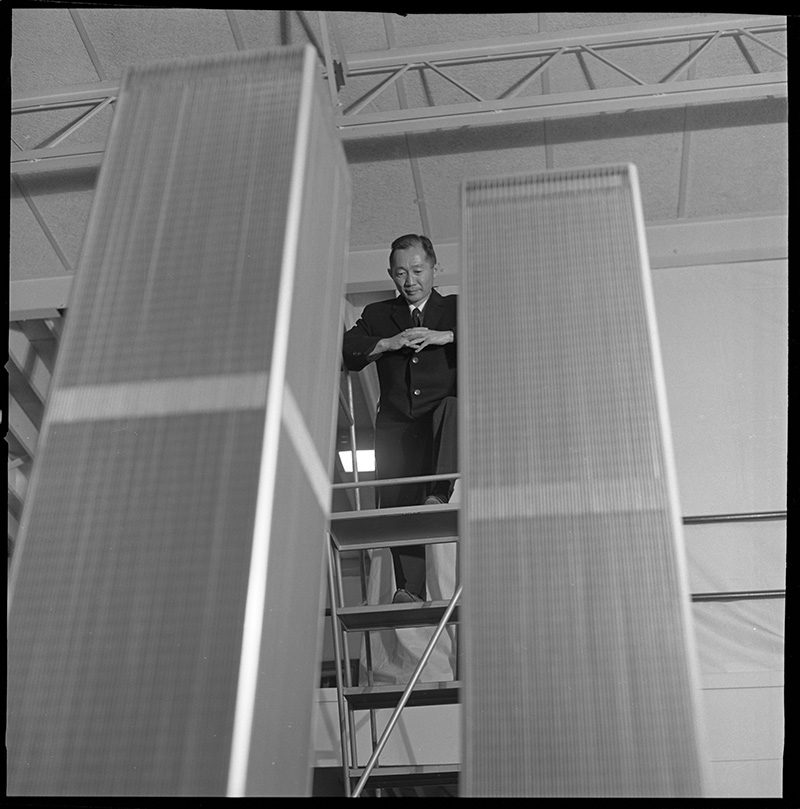

Although best remembered as the architect of the 110-story in New York City that were destroyed by the terrorist attacks on 9/11, first-generation Japanese American built his legacy in Detroit while designing daring and noteworthy buildings before being acknowledged as one of the greatest architects of the 20th century.

Among his important buildings in the Detroit area are four on the Wayne State University campus (, 1958; , 1958; , 1960; and , 1964); the (One Woodward), 1963; and the synagogue off Telegraph Road in Bloomfield Township, 1973.

âYama was one of the architects who defined midcentury modernism, and he brought it to Detroit,â says former Detroit Free Press journalist John Gallagher, the author of (Wayne State University Press, 2015). âHe often achieved a more humanistic type of architecture based upon his great mantra, âSerenity, surprise, and delight.â All of his great buildings include a connection to natural daylight, tall windows, outdoor plazas, water features, and sculpture gardens.â

By his own account, Yamasaki and his team designed over 250 buildings throughout the world, including schools, offices, churches, and homes, though he admits in his autobiography that some of them were âbad.â

Born and raised in Seattle, Yamasaki worked in Alaskan canneries during the Depression to pay for tuition at the University of Washington, where he obtained an architecture degree in 1934 before starting his career at several firms in New York City.

In 1945, he moved to Detroit when he was hired as chief designer at Smith, Hinchman & Grylls (now ).

He soon made his mark locally in 1951 with his design of the contemporary and cutting-edge eight-story covered in a glassy facade. âIt was the first modernist building in Detroit, and everything built after that was really in a modernist mode,â Gallagher says. âAfter Albert Kahn, who had the biggest influence in Detroit, I believe Yama is second in terms of influence and what he did.â

Although he had faced discrimination for much of his life, Yamasaki especially suffered anti-Asian prejudice at the end of World War II, when real estate agents would not help him find a home for his family in Grosse Pointe, Birmingham, or Bloomfield Hills. By 1947, he was finally able to purchase a farmhouse for his family in undeveloped Troy, before designing and moving into his own Bloomfield Township home in 1972.

In 1949, Yamasaki and colleagues George Hellmuth and Joseph Leinweber formed their own firm, where they earned national attention for Yamasakiâs celebrated arched terminal design for the (1956) that inspired future modern airport terminals and earned the first of his three .

Yamasaki garnered further national recognition with his ânew formalistâ design for his iconic Detroit masterpiece, the McGregor Memorial Conference Center at Wayne State University. Set on a raised platform, it embodies his âserenityâ vision of using light, sculpture, and water along with what became his famous repeated geometric patterns and pointed Gothic arches. The work led to further commissions on the campus for three other buildings and a master plan that transformed the campus. In 2015, the McGregor building was designated a National Historic Landmark.

By the late â50s, Yamasaki had started his own firm in Troy and continued to secure other notable commissions, including his first skyscraper, the 30-story at Woodward and Jefferson avenues, the only one he designed prior to the World Trade Center.

âThere is a continuum in Yamaâs work, and he would often borrow elements from one building to another. You can see how the World Trade Center design follows from the Michigan Consolidated Gas Building,â Gallagher says.

Yamasakiâs prominence continued to rise with his daring design of the () built for the 1962 Seattle Worldâs Fair. A year later, at age 51, he received worldwide fame when he graced the Jan. 18 cover of, four months after receiving the commission from the New York Port Authority to build what became the World Trade Centerâs twin towers. When the seven-building complex opened in 1973, the towers â One World Trade Center, at 1,368 feet, and Two World Trade Center, at 1,362 feet â were the tallest office buildings in the world.

Other notable Yamasaki projects include the (1961); the (1975); and (1977), among others.

A member of the prestigious and an , Yamasaki died of cancer at Henry Ford Hospital on Feb. 6, 1986. He left behind his wife, Teri; a daughter, Carol; and two sons, Kim and Taro.

After Yamasakiâs Troy firm entered receivership in 2010, the company records were rescued and are now located at the in Lansing. The same year, the family donated his personal papers to the at Wayne State University.

** Editorâs note: An earlier version of this article said that Yamasakiâs Troy location closed in 2010. It actually went into receivership in 2010, and we have since updated the article with the correct information. Ìý

This story originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of Â鶹·¬ºÅ Detroit magazine. To read more, pick up a copy of Â鶹·¬ºÅ Detroit at a local retail outlet. OurÌýdigital editionÌýwill be available on May 6.Ìý

|

| Ìý |

|