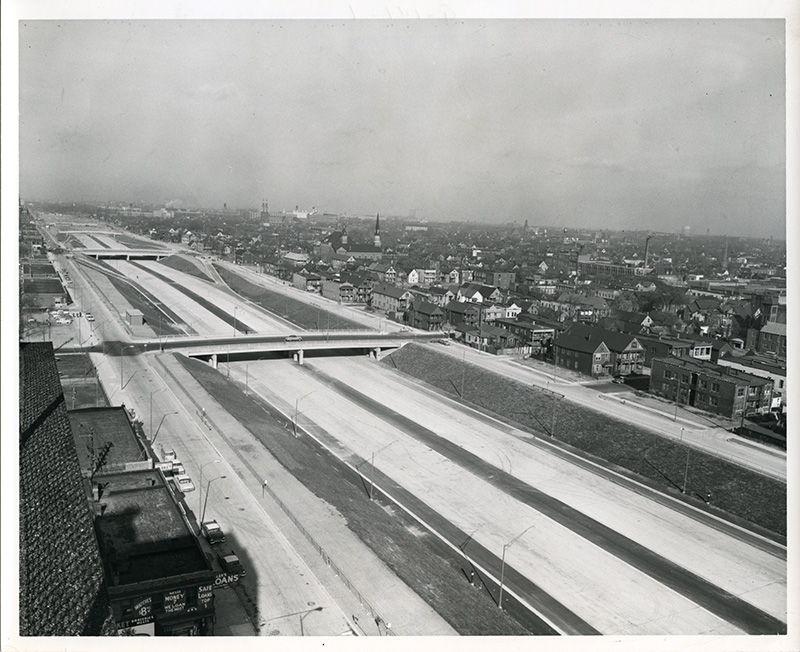

In 1964, the 1-mile highway of I-375 stretching north from Jefferson to Mack Avenue was built without the consent of the neighborhoods it destroyed. That wasn’t unusual for the time: Highways that crisscross Detroit — like many across the country — were created by forcibly removing the people who lived in the new roads’ slated paths. It happened frequently in America, part of a process known as “urban renewal,” which author James Baldwin famously quipped was code for “Negro removal.”

But when they were established, freeways didn’t just relocate people. They forced businesses and schools to close and erased a culture shaping entire neighborhoods. In the process, they often destroyed burgeoning wealth, preventing hard-to-come-by capital from accumulating for Black Americans and their future descendants.

One of Detroit’s most glaring examples of “urban renewal” is I-375. The highway destroyed and , spaces where many Black Detroiters lived, worked, and played — spaces that the now plans to alter again.

Initially believed to be a prime opportunity for reconciliation and a chance to reconnect downtown with parts of the east side, MDOT’s is set to build a six-lane (at times expanding to nine-lane) boulevard with exhibits honoring those who lived in Black Bottom and Paradise Valley. MDOT says the new road will improve traffic safety and easily allow pedestrians, cyclists, and cars to access downtown.

Its plans have stirred controversy, as many urban planners, local stakeholders, downtown business leaders, and advocates want MDOT to stop the project altogether and begin again with increased community input. That’s because dissatisfaction with the project ranges widely, with some wanting a bigger focus on reparations for those displaced by the highway’s creation, others desiring something safer than a six-lane boulevard, and still more hoping the highway isn’t removed at all.

But regardless of their differences, many believe nearby residents, and those originally displaced by the highway, should decide I-375’s fate.

Wrong-Way Street?

Marvin Beatty is part of a growing chorus of Detroiters hoping to stop the project altogether and begin anew with more serious consideration of residents and businesses that neighbor the highway. That’s because Beatty, vice president of community and public relations for , says resident perspectives haven’t been adequately included in shaping the project.

“There are a bunch of people who are obviously sitting in a room and throwing darts on a wall and telling us, ultimately, what this is all going to look like when it’s done. But what’s going to happen while it’s under construction?” Beatty asks. “What’s going to be the level of devastation while it’s under construction?”

For decades, the predominately African American Black Bottom was a residential area complementing Paradise Valley, its neighboring business corridor. In total, the two spaces comprised 129 acres and were home to hundreds of drugstores, restaurants, churches, banks, and barbershops. Three hundred of the area’s businesses were Black-owned, but when I-375 was built, states, all of them were demolished and 130,000 people were displaced.

Bert Dearing Jr., a Black Bottom native and owner of , remembers the neighborhood well. “Black men owned everything in Paradise Valley. I mean, the clubs, everything was Black-owned,” Dearing told s Nick Austin. “All the musicians that came in town — Black or white — came to Black Bottom. It was a special place.”

Among the displaced, 92% were Black Bottom renters — constituting a majority of the area’s residents — who never received compensation, the same report reads. The results, Beatty says, were stark: Wealth was destroyed as Black Detroiters scrambled to re-create opportunities that remained limited due to pervasive segregation and discrimination.

“The devastation that literally took place in an area that was fully populated — great restaurants, nice hotels, Black hotels, Black restaurants, funeral homes, drugstores — everything that would sustain a community for its viability was uprooted and given crumbs … to go away.”

Balancing Safety and History

MDOT has been developing plans to replace I-375 since at least 2014, when it conducted a planning study with several local partnering agencies to inquire about alternative designs for what is now a spur of I-75 into downtown Detroit. But the plans gained wider attention over one year ago when U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg came to Detroit to announce his agency’s delivery of $104.6 million for the project. It was then that Buttigieg said the project would be part of a “reparative process,” giving a nod to those who lived in Black Bottom and Paradise Valley. The city of Detroit echoed a similar sentiment that day.

But the leader of the project, MDOT, has never used such language, saying only that the agency will “pay tribute” to Black Bottom and Paradise Valley residents. It claims that 30 acres of land will be created by the highway’s removal and that community enhancement projects, which haven’t yet been detailed, will be funded.

Instead, MDOT has focused primarily on promoting safe, multimodal travel for cyclists, pedestrians, and large vehicles. Rob Morosi, MDOT’s communications specialist for the metro region, says his agency is doing everything it can to provide a safer flow of traffic for all those who will use the new road.

“And while some may feel that the boulevard is not the right option to connect neighborhoods on the east side to the central business district, we are diligently providing safe options for all modes of transportation through our design,” he wrote in an email to Â鶹·¬şĹ Detroit.

Although some are displeased with its outreach efforts, MDOT has been holding regular community input meetings on the I-375 project for the past year. Leslie Love, MDOT metro region assistant deputy director, says that in August 2023, she met an 80-year-old woman and former Black Bottom resident at one of the project’s open meetings. She calls that woman, and attendees like her, “advisers” for the project.

“We are not interested in repeating negative history, and we strive, in this project, to be engaged in community,” Love says.

Reversing an Injustice

But 60 years after I-375’s creation — after the public murder of George Floyd, protests for Black lives, widespread calls for reparations for Black Americans, and the creation of the — many want to use the I-375 project as an opportunity for something more restorative. They believe negative history is, in fact, being repeated and that city resident perspectives are being ignored by MDOT.

That’s partly why around Detroit, local think tanks, columnists, urban planners, and community groups have called MDOT’s project a missed opportunity. The purpose of the project, they claim, should be to repair the original harms created by the highway — to do something to make the displaced people and their descendants whole by restoring the wealth that was destroyed. Instead, they see little more than an infrastructure plan messaged as something else.

“This is a massive traffic engineering project that was never rooted in justice, equity, or reparative action, and it’s an insult to watch it be packaged like it was or ever could be,” Paul Jones III, a native Detroiter and urban planner, wrote for .

If MDOT did alter the project’s goals, the department would likely have to find more money elsewhere, potentially diminishing its resources for existing projects, says Todd Scott, executive director of the and a member of the project’s advisory committee.

It’s not just the lack of reparations disturbing residents and advocates. Some Detroiters don’t believe the boulevard will increase traffic safety and don’t want the highway removed at all.

Scott says current plans don’t allow pedestrians and cyclists to access downtown safely from parts of the east side. “People are having to cross these very large intersections [under the new plan], and that’s generally unsafe,” he says.

At a public meeting in April 2023, attendees had similar opinions. One person commented that the planned boulevard is “more dangerous for pedestrians than the freeway.” Still, MDOT has not altered its plans.

Janet Webster Jones, who lives in Lafayette Park, which neighbors I-375 and was created when the freeway was built, fears the value of her neighborhood will decline and people will struggle to navigate the east side if the highway is removed. She wants I-375 to be repaired, not replaced.

“Now what you’re going to do is disrupt the travel patterns of people who adjusted themselves to the mistake that was made, and then a new disruption will come along with a new generation of people,” she says.

Stop, Look, Listen

Construction on I-375 is expected to begin in 2025 and conclude two years later. But a number of Detroiters, including Beatty and Jones, are calling on MDOT to start its project over and lead more responsibly with the perspectives of people who neighbor the highway — a sentiment echoed at a November Detroit City Council meeting about the I-375 removal project. Leading with the perspectives of directly impacted people could mean a lot of different things, but it starts, according to a report from the think tank, by listening to community members with direct ties to Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, and those currently living near I-375, so the community can help design the project from the ground up.

That’s not unheard of: St. Paul, Minnesota, and New Orleans have been starting their highway-removal projects with people who neighbor the highways that are targeted for removal.

From there, Detroit Future City CEO Anika Goss says there are many tangible reparations

proposals that state and federal officials can explore, including paying Black Detroiters to remove the highway, ensuring Black Detroiters get future available land sales, and creating a fund that benefits both small and large Black businesses once the highway is removed. Doing reparative work, she says, is necessary to righting past wrongs and to injecting capital back into the neighborhoods that once had it.

Goss believes MDOT should slow down or stop the project altogether and align itself with the priorities of city residents. “This is not a social program. This is investment. Reparative investments are investments that restore the wealth that was lost. MDOT may feel like they’ve done their due diligence in order to move forward with this project, but no one else does. And because of the historical significance of this project, we can’t just let this slide.”

This story is from the February 2024 issue of Â鶹·¬şĹ Detroit magazine. Read more in our digital edition.

|

| Ěý |

|