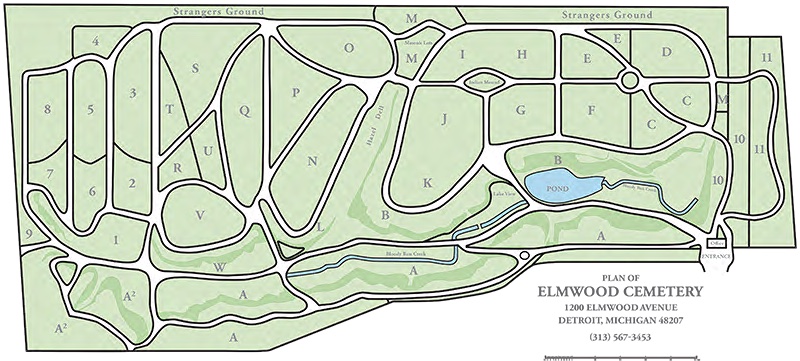

Many metro area motorists slow to marvel at the verdant grounds and imposing Gothic Revival monuments lining west Mount Elliott Street in southeast Detroit, but few realize they’re admiring 86 acres of history.

has been in operation for more than 175 years, making it the city’s oldest nondenominational necropolis. The site, once a battlefield in a failed 1763 British effort to break the Ottawa tribal chief Pontiac’s siege of Fort Detroit, became the final resting place of choice for many Michigan giants, starting in 1846. Here are some of the bold-faced names etched in stone across the Elmwood expanse.

Lewis Cass (1782-1866)

Buried in Section A, Lot 75

Lewis Cass was arguably the state’s most powerful political figure of the 19th century.

Elected to the Ohio House of Representatives in 1806, at age 24, Cass fought in the War of 1812 and rose to the rank of brigadier general. In 1813, President James Madison appointed him as governor of the Territory of Michigan. In that role for over 18 years, Cass struck treaties with indigenous tribes that led to the U.S. acquisition of most of their lands in the territory. He helped Michigan become the 26th U.S. state, in 1837.

Cass, the Democrats’ unsuccessful nominee for president in 1848, was secretary of war under President Andrew Jackson, secretary of state for President James Buchanan, and a U.S. senator from Michigan.

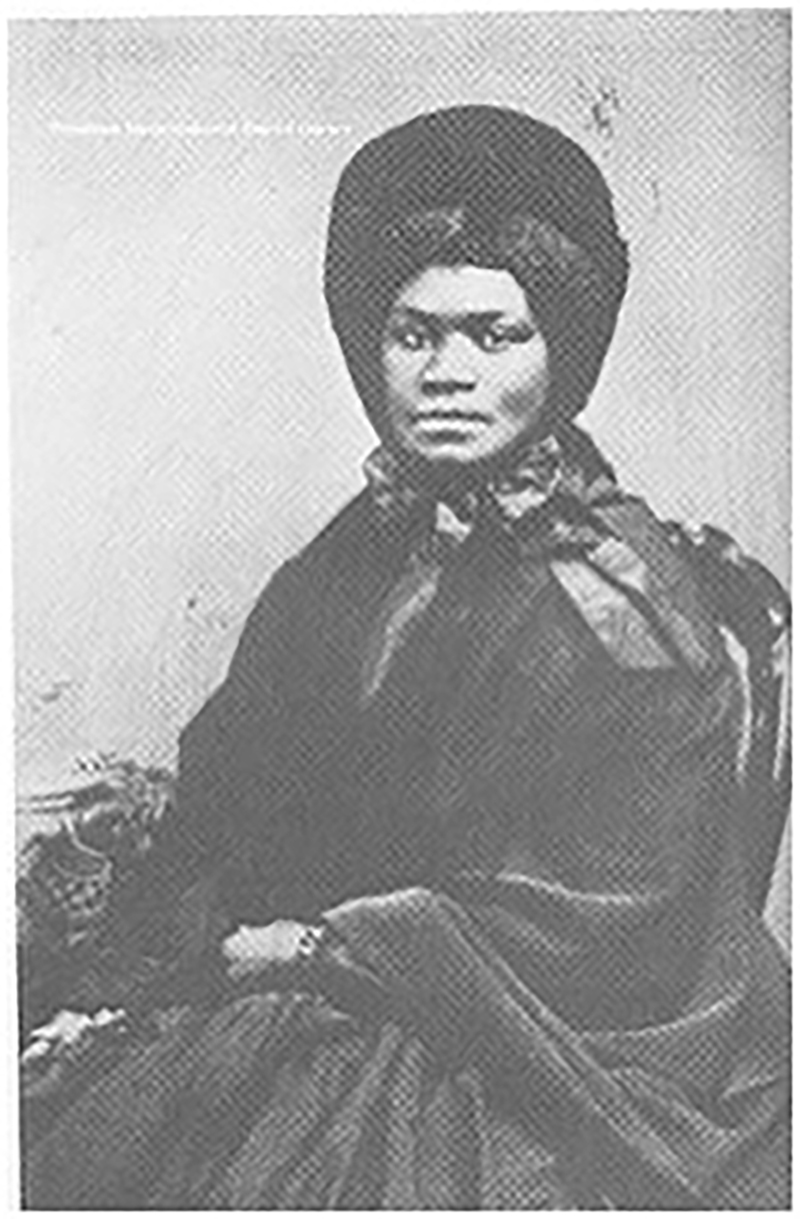

Elizabeth Denison Forth (1793-1866)

Buried in Stranger’s Ground T-45/G194

Elizabeth “Lisette” Denison Forth was born enslaved on a farm along the Clinton River near Detroit. By the time she died, she had become a barrier-breaking landowner, stockholder, and philanthropist.

Five years after escaping to Canada to gain her freedom, Forth returned to Michigan to work as a domestic servant for some of the most prominent Detroiters of the time, including Mayors Solomon Sibley and John Biddle. Through them, she connected with distinguished bankers and politicians, who helped her invest her wages.

By 1825, she had earned enough to purchase 48.5 acres of land in Pontiac — an acquisition that made her the first Black woman in Michigan to own property. Forth would also buy stock in other plots of land, as well as in two local banks and a steamboat.

Upon her death, Forth left much of her estate to the construction of the St. James Episcopal Church in Grosse Ile. It was fitted with distinctive red doors, as a tribute to Forth, and still stands today.

George DeBaptiste (1815-1875)

Buried in Section C, Lot 24

This entrepreneur and real estate owner secured his place in history as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, which helped enslaved people escape North, to freedom. He is honored with a statue in Hart Plaza, in Detroit.

DeBaptiste, born a free Black man in Virginia, co-founded Detroit’s first civil rights organization,Ěý the Colored Vigilant Committee, formed the first Michigan Colored Regiment to fight in the Civil War, and in his youth, was valet to President William Henry Harrison. DeBaptiste held his hand when he became the first president to die in office, in 1841.

As a superintendent of the Underground Railroad in the antebellum U.S., DeBaptiste helped transport hundreds of enslaved people to Canada, via his own steamship, the T. Whitney.

Margaret MatherĚý(1859-1898)

Buried in Lot 134, Section 3

Margaret Mather rose from impoverished Detroit origins to become one of America’s most famous Shakespearean actresses of the 1880s.Ěý

Her 1885 Broadway debut in Romeo and Juliet drew attention almost immediately. The unexpected force and physicality she brought to the character delighted audiences but drew mixed reviews — a trend that would persist throughout her career. The show ran for a record-setting 84 performances.

Later, she toured North America, starring in several stage productions, including John Augustin Daly’s Leah the Forsaken and Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Lady of Lyons.Ěý

Mather would die of kidney failure, after collapsing on stage while portraying Imogen in Shakespeare’s Cymbeline. She was buried in the white costume gown she had worn as Juliet.

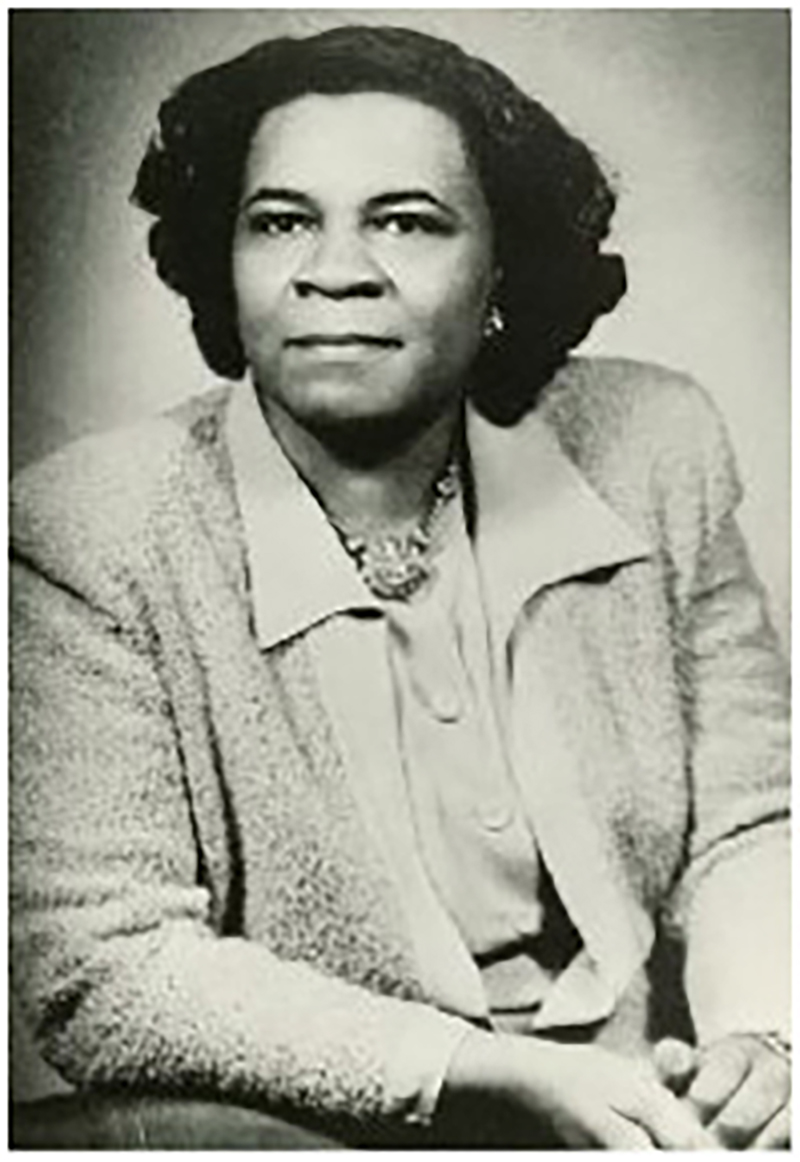

Rosa Slade GraggĚý(1904-1989)

Buried in Section A2, Lot 200

Civic leader Rosa Slade Gragg was a trailblazing woman of firsts. In 1947, she founded the first Black vocational school in Detroit, the Slade-Gragg Academy of Practical Arts, aka the “Tuskegee of the North.” She was the first Black president of the Detroit Public Welfare Commission, helped open Detroit’s first Civilian Defense Office, and was president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. In that role, she oversaw the opening of several women’s health clinics in Washington, D.C., and got the Fredrick Douglass home declared a historic site.Ěý

Slade Gragg, an advisor to FDR, JFK, and LBJ, was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame.Ěý

The Rev. Charleszetta Waddles (1912-2001)

Buried in Section S, Lot 109

Charleszetta Waddles, known affectionately as “Mother Waddles,” grew up poor, an experience that inspired a lifelong passion for helping the destitute. Her devotion to this cause would earn her numerous honors, including the Sojourner Truth Award, the Religious Heritage Award, the National Urban League’s Humanitarian Award, and letters of commendation from President Nixon and two U.S. vice presidents.

Waddles’ legacy of compassion began when she became determined to help a neighbor on the verge of losing her home. By canvassing the neighborhood for donations, Waddles gathered enough food and money to feed the woman and her two children for eight weeks. In 1950, she established the Helping Hand Restaurant in Detroit, to offer meals for as little as 35 cents. It closed in 1984, after a fire.

An ordained minister, she launched Mother Waddles Perpetual Mission, in 1956. The nonprofit offered a free medical clinic, job counseling and placement, and classes teaching skills such as typing, dressmaking, cooking, and upholstery. ItĚýremains active and serves some 90,000 people each year.

Erma HendersonĚý(1917-2009)

Entombed in Gallery A, Level E, Niche 8

Erma Henderson became the first Black person to defeat a white opponent for a seat on the Detroit City Council, in 1972. As longtime council president, she was regarded as the city’s most powerful woman.

In 1975, Henderson targeted racial discrimination in real estate and housing, organizing the Michigan Statewide Coalition Against Redlining and successfully getting the practice outlawed.

Prior to her election, she served as executive director of the Equal Justice Council, which collected judicial data — efforts that helped ensure Blacks received fair treatment by the criminal justice system, following the 1967 Detroit rebellion. She also organized the unprecedented 1982 Continental African Chamber of Commerce Michigan Chapter’s International Trade Conference. The event lasted four days and brought together ambassadors of finance from 23 African nations.

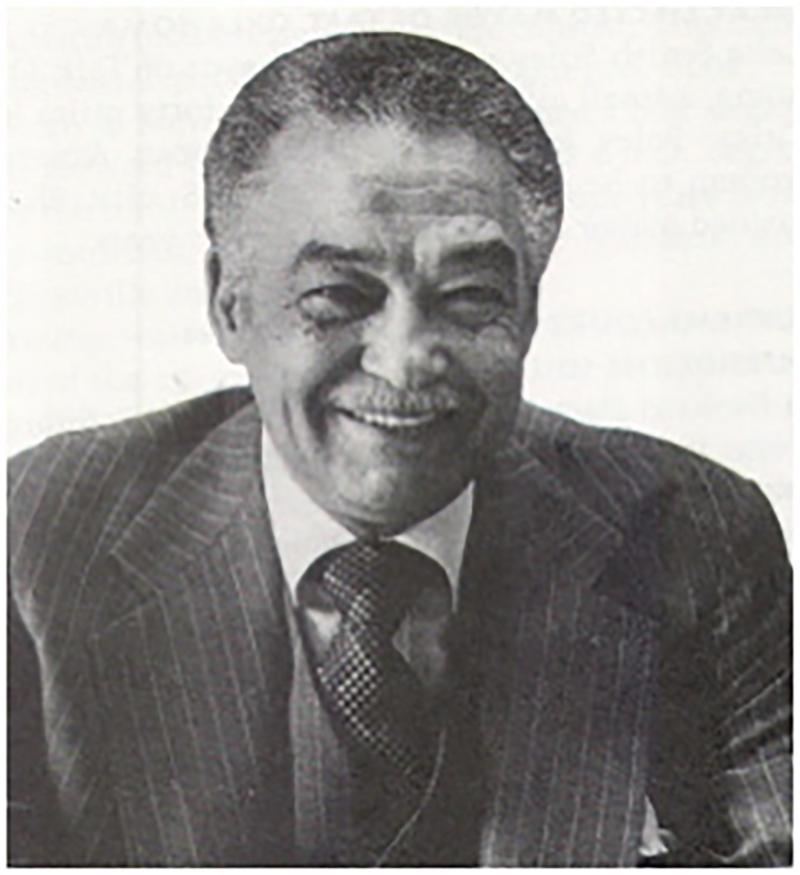

Coleman A. Young (1918-1997)

Buried in the Hazel Dell Section

Detroit’s first Black mayor, Coleman A. Young served a record five terms from 1974 to 1994. While in office, Young reduced crime rates, curtailed police brutality, integrated city departments, and led construction projects —including the Joe Louis Arena and the Renaissance Center.

Prior to politics, Young was a well-known labor leader, serving as director of organization for the Wayne County branch of the Congress of Industrial Organizations. He was also a civil rights activist and a bombardier with the Tuskegee Airmen, during World War II. The NAACP recognized Young’s many accomplishments by awarding him the Spingarn Medal for outstanding achievement, in 1981.

Dr. CharlesĚýH. Wright (1918-2002)

Buried in Section 10, Lot 95

Dr. Charles H. Wright is best known for spearheading the integration of Detroit hospitals and founding the — one of the largest Black history museums in the U.S.

In addition to practicing medicine locally for 35 years, Wright co-founded the African Medical Education Fund to enable African nationals to study medicine in the U.S., traveled to the South to treat patients during civil rights marches, and tended to the ill aboard the S.S. Hope, a Columbian floating hospital.

After retiring from his practice, Wright wrote several books, including a historical account of Black people in Detroit’s health care system, The National Medical Association Demands Equal Opportunity: Nothing More, Nothing Less.Ěý

This story has been updated for 2023, but was originally featured in the December 2021 issue of Â鶹·¬şĹ Detroit magazine. Read more stories in ourĚýdigital edition.

|

| Ěý |

|