Chef and cookbook author Jon Kung has a confession to make.

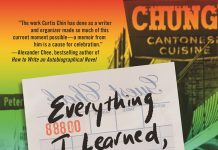

âI donât read a lot of headnotes in recipes,â says Kung, whose debut cookbook, , is being released this month.

âThe types of books that I like to read are textbooks and reference books. Iâm not looking for techniques. ⦠Iâm looking for explanations on chemical reactions to inform my recipes.â

Nevertheless, youâll want to read the headnotes and all the other words in Kungâs new cookbook. The Detroit-based chef shares the signature flavors, intelligent wit, and easygoing presence that have made them a social media sensation. The prolific content creatorâs cooking lessons on TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram during the early, isolating days of the COVID-19 pandemic garnered millions of likes and many millions of followers, leading to a book deal.

Kung Food takes their cuisine from screen to page. Dishes like Faygo Orange Chicken, Dan Dan Lasagna, and Thanksgiving Turkey Congee typify their take on âthird-cultureâ cooking, based on the idea that the culture of someoneâs home is not the same as the culture of the country where someone lives or where their parents are from.

The term âthird-culture kidâ was coined by American sociologist Ruth Useem in the 1950s to describe expat children who grow up overseas and are exposed to different cultures that coalesce. Kung is the perfect example, having been born in Hong Kong and raised in Los Angeles and Toronto.

âI wanted to distill what American Chinese food through my lens was going to be like, and obviously it was a lot more internationally focused, but still pretty rooted in what I consider to be American food.â

Kung was doing third-culture cooking as well as grinding and hustling on the Detroit food scene long before their first TikTok went viral.

Growing up in Los Angeles and Hong Kong, Kung experienced good food early thanks to dining out with their parents and attending Sunday dinners at their grandparentsâ house. Kung is mostly self taught but gained professional cooking experience through gigs like a stage (internship) at , and local kitchen jobs at Gold Cash Gold and .

Law school brought Kung to Detroit in 2007, but the food community rooted them here as they continued to refine their cooking, inspired by nostalgia and flavors they grew up with. They wouldÌýhost secret pop-up dinners and dumpling-making classes at their Eastern Market studio, along with Saturday brunches (as Kung says in the book, stop asking if theyâll bring back the brunches, because âthey were very illegalâ).

By 2014, Kung was an established chef on the pop-up circuit, their resume including pop-ups alongside Lady of the House chef Kate Williams. Diners in Detroit wanted more diversity, and that helped propel pop-ups like , with its creative take on Chinese-American food.

âEverybody was cooking more internationally,â Kung recalls. âYouâd be going to these New American restaurants and gastropubs, and it was just a bunch of mostly white male chefs, taking ingredients from all of the surrounding neighborhoods and different cultures and distilling it through their lens. And I was like, âWhy canât I do it through mine as a Chinese American?ââ

Through the book, Kung hopes to plant that seed in other aspiring chefs looking to represent their cultures through food.

âHopefully that could give rise to a whole different kind of American cooking where the immigrant experience is the center because the immigrant experience is the American experience,â Kung says. âAnd to put focus on that, to showcase not just our diversity but our proximity to each other.â

Kung Food is equal parts tongue in cheek (see the recipe for Glam Trash Cake Rangoons) and educational (e.g., âRead This Before Cooking Anything in a Wok!â offers a step-by-step guide on how to properly season and clean a wok). In the introduction, Kung writes, with typical irreverence: âHere ends the disclaimer that every POC cookbook author has to write because culturally insecure people on the Internet love to call to question their authenticity just because we donât cook exactly the way they do, or their grandma did.â

Kung explains: âAuthenticity itself in regards to food really takes our experiences into consideration and our experiences with each other and through that, I think, produces a whole different other cuisine that is truthful and vibrant.â

One headnote in particular shows what can happen when you donât subscribe to a rigid view of what food should be. In the book, Kung describes how their chef-teacher used Jif peanut butterÌýin her dan dan noodles with egg because this particular brandâs inherent sweetness removes the step of adding sugar to balance the sauce.

âI donât make my dan dan noodles with Jif as they did there,â Kung writes. âBut it was an important lesson to me in putting recipes on pedestals. ⦠Sometimes, being clever and pragmatic is the most âauthenticâ way to make anything.â

The second-to-last chapter, âKung Foo Means âwith Effort,ââ features popular recipes like Hong Kong Style Chicken and Waffles. Kung hopes readers will cook the basic recipes and proceed to find their own signature dishes, as Kung did, taking inspiration from other dishes and techniques and putting their own spin on them.

âI really would love to be tagged in someoneâs Instagram post where somebody was like, âI

took your chili oil, and I made something really different with it.â That is something that bridges our structures together. Thatâs the whole thesis of this book: Here are some basic flavor profiles that I have grown up with. And the rest of the book is an example of what you can do with it.â

This story is from the October 2023Ìýissue of Â鶹·¬ºÅ Detroit magazine. Read more in our digital edition.

|

| Ìý |

|