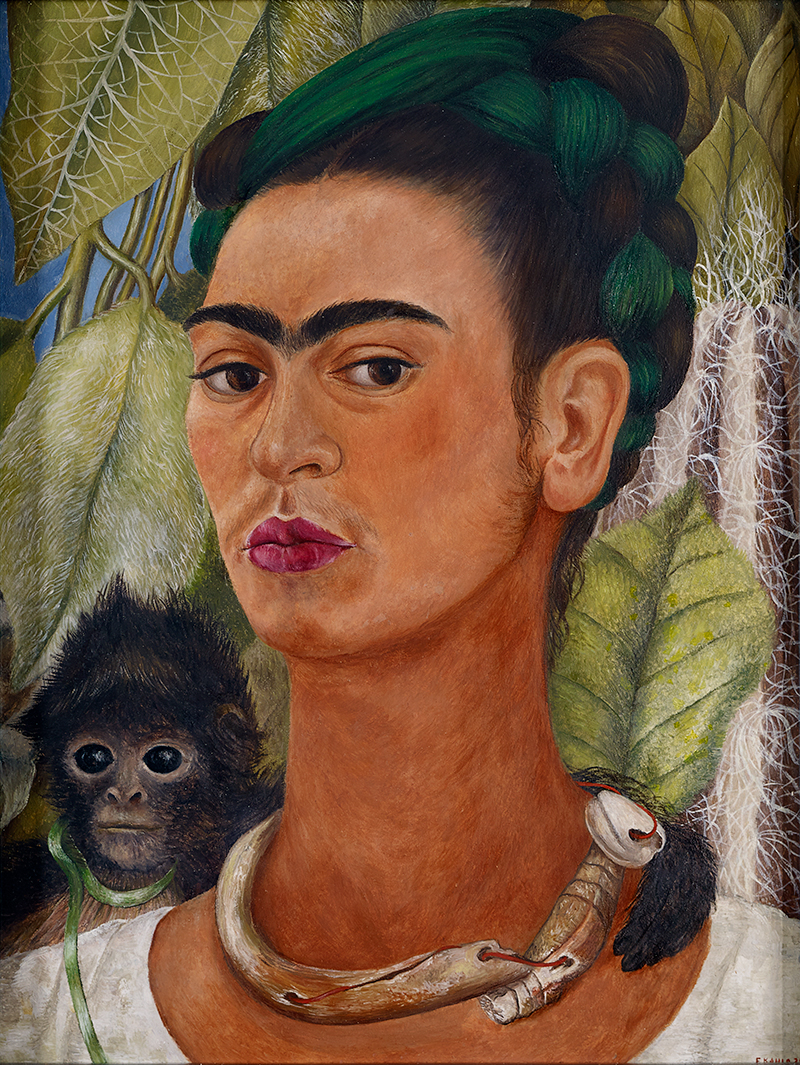

Want a peek at Frida Kahlo’s work close to home? The Mexican artist’s 1938 painting “Self-Portrait with Monkey” is on view as part of the Detroit Institute of Arts’ exhibit Guests of Honor: Frida Kahlo and Salvador DalĂ through Sept. 27.Ěý We asked the DIA’s Dorota Chudzicka, assistant curator of modern European art, to help us understand the piece and what it tells us about Kahlo’s vision.

So, what’s up with the monkey?

“Kahlo often painted herself with small spider monkeys that she and her husband, Diego Rivera, kept as pets. Having almost human qualities, they are her animal alter egos. Monkeys also carry broader cultural significance. In Christian and Mayan art they were associated with sin, promiscuity, and the dangers of excessive love.”

Why does she look so, well, surly?

“The painting is composed in the rigidly frontal manner of 19th-century Mexican provincial portraits. With her hair up and an inscrutable facial expression, Kahlo challenges the viewer with her intense gaze, amplified by the stare of her monkey, Fulang Chang. The painting is about looking, with a sense of ambiguity about who is regarding whom.”

What’s she wearingĚýaround her neck?

“Kahlo’s elongated neck bears a pre-Columbian wood-and-shell neckless. It and Kahlo’s attire together reference her Mexican heritage, particularly the economically and socially independent women of Tehuantepec, who came to symbolize the ideal of freedom embodied by the indigenous culture inĚý post-revolutionary Mexico.”

Tell us about the unibrow.

“Kahlo’s ungroomed eyebrows were a signature feature of her self-fashioned persona, a sign of her devotion to Mexican culture and to the ideal of beauty represented by indigenous women. She also exaggerated her mustache to emphasize her androgynous appearance and ambiguous gender identity.”

|

| Ěý |

|